Music journalism, books and more

Around the world on a 45 rpm disc

“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness,” Mark Twain wrote. It also has the power to awaken the senses. In 1962, I was an innocent abroad, a white boy plucked from homogenous suburban Toronto and deposited in the tropical, northern Malayan town of Ipoh.

My father, born there during colonial times, had decided to move us to his hometown while he embarked on a writing project and explored his ancestral roots. I can still vividly remember all the exotic smells, sights and sounds of the place. A walk through Ipoh’s streets, past food stalls selling aromatic curries and spiky rambutans, dodging trishaw peddlers and pedestrians in sarongs and chongsams, gawking at Chinese cinema posters and lavish Indian mosques, was wildly carnivalesque. More dizzying and thrilling than anything I’d experienced on the CNE Midway.

It was during that year in Ipoh, with my senses working overtime, that I became keenly aware of music. My sisters and I, like other ex-pat kids, spent many hours at the Cathay theatre watching English-dubbed Chinese films and occasional British movies like South Pacific and The Guns of Navarone, mostly family or grown-up titles. The exception was The Young Ones, a musical starring England’s teen idol Cliff Richard and his group the Shadows and clearly aimed at us.

It wasn’t until much later that I found out what a huge impact Cliff Richard & the Shadows had on Singaporean and Malaysian pop music, with garage-rock bands like Rocky Teoh & the Falcons and Boy & his Rollin’ Kids.

It wasn’t until much later that I found out what a huge impact Cliff Richard & the Shadows had on Singaporean and Malaysian pop music, with garage-rock bands like Rocky Teoh & the Falcons and Boy & his Rollin’ Kids.

The biggest hit in Ipoh that year was “Bengawan Solo” by Anneke Grönloh, a pop singer from the Dutch East Indies colony that had become Indonesia. Sung seductively in Indonesian, with saucy horns, insouciant strings and what was, for the time and place, a daringly swinging beat, it danced out of doorways and floated through the streets. I had no clue what it was about, but didn’t care: the unfamiliar language, melody and rhythm had me hooked. I even tried to sing the words (which turned out to be a nostalgic longing for the Solo River in Java) and carry the tune (drawn from the kroncong folk style of Javanese music).

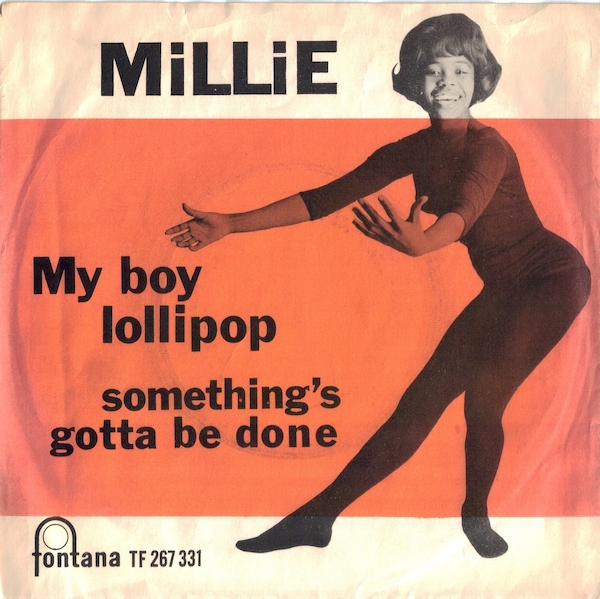

In 1963 my family moved on to England, living in London during the year that the Beatles broke, and music from that point on became an essential part of my life. My listening tastes grew ever more eclectic: ska from Millie Small’s “My Boy Lollipop” onward, bossa nova via Astrud Gilberto’s “The Girl from Ipanema.” Later I absorbed cumbia, compliments of Los Lobos’ magic-realism classic “Kiko and the Lavender Moon,” and ragga-bhangra, from “Chok There” by Apache Indian, the UK singer who was briefly “hotter than vindaloo” in the early ’90s.

Non-English songs never seemed like closed doors. Some, like Kyu Sakamoto’s “Sukiyaki,” King Sunny Ade’s “Ja Funmi,” Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s “Mustt Mustt” and PSY’s “Gangnam Style,” were addictive because of their undeniable sweetness, inherent groove or sheer wackiness. Anneke Grönloh’s “Bengawan Solo” went on to become one of Southeast Asia’s most famous and beloved songs, with numerous versions sung in Chinese and Japanese. For me, that unassuming little 45 turned out to be my gateway into a big wide world of music that, like the universe itself, just keeps on expanding.