Music journalism, books and more

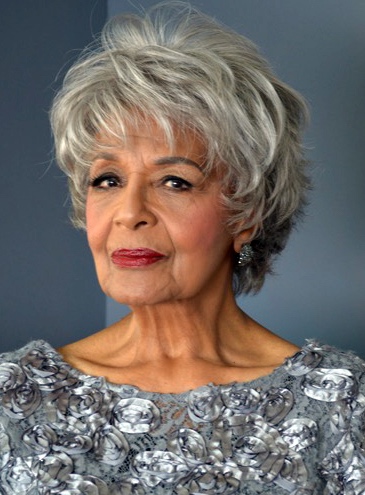

Eleanor Collins - Trailblazing jazz singer overcame racism with quiet dignity

From her birth as a daughter of Black settlers in the early 20th century to recognition as Vancouver’s first lady of jazz, Eleanor Collins was a trailblazer in music and African-Canadian history.

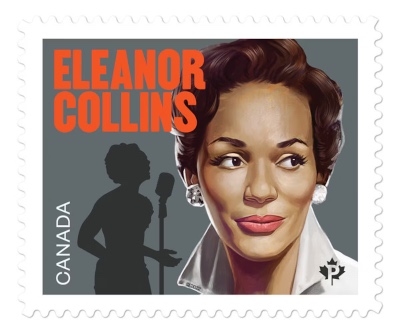

Her role in breaking new ground for women and Black performers earned her membership in the Order of Canada in 2014. Then, in 2022, Canada Post featured Ms. Collins on a stamp, honouring her as the first Black Canadian entertainer – and first female Canadian singer – to star in her own nationally broadcast TV series, The Eleanor Show.

Acknowledging the honour, Ms. Collins said she had no sense of her pioneering role back then. “We each did what we felt we were called to do – live in the present and make the best decisions we could in support of that,” she recalled in her typically humble way. “How history regards or records our lives in retrospect, in reflection, is up to history.”

Ms. Collins died on March 3, in a Surrey, B.C. hospital, at the grand age of 104. Among the many ways she is being remembered is as a principled woman who chose family over fame. “Eleanor could have been as well-known as Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday or Sarah Vaughan if she’d pursued a career in the United States – she was on that level,” says Paolo Pietropaolo, host of CBC Radio’s In Concert. “But she chose to stay here because of her family and community. That’s pretty extraordinary.”

For Handel Wright, director of the University of British Columbia’s Centre for Culture, Identity and Education, Ms. Collins’s life exemplifies grace and dignity. “Her family faced prejudice when they first moved to Burnaby, an all-white Vancouver suburb at the time, and were greeted by a petition calling for them to move,” Mr. Wright observed. “But Eleanor, a mother of four, threw herself into community work, volunteering by teaching music to local kids, and wound up winning over her neighbours and gaining their respect. She confronted racism in her own quiet and beautiful way.”

For Handel Wright, director of the University of British Columbia’s Centre for Culture, Identity and Education, Ms. Collins’s life exemplifies grace and dignity. “Her family faced prejudice when they first moved to Burnaby, an all-white Vancouver suburb at the time, and were greeted by a petition calling for them to move,” Mr. Wright observed. “But Eleanor, a mother of four, threw herself into community work, volunteering by teaching music to local kids, and wound up winning over her neighbours and gaining their respect. She confronted racism in her own quiet and beautiful way.”

Added her daughter, actor Judith Maxie: “She believed it was a way for others to get to know a minority-race person and see that we shared many of the same values and thus our similarities were always greater than our differences.”

Principled and pioneering ways came honestly to Ms. Collins. She was the second of three daughters born in Edmonton to Richard Ellis Proctor and the former Estelle Mae Cowan, Black settlers whose families had fled Ohio and Kansas in 1909 to carve out a better life north of the border.

Eleanor was born Elnora Ruth Proctor on Nov. 21, 1919, joining her sister Ruby and followed by Pearl. Her father delivered furniture with a horse and dray wagon, until an injury forced him out of work. To make ends meet, Estelle started an in-home hand laundry service and put her daughters to work.

Together with her sisters, Eleanor gravitated to music and singalongs of hymns and spirituals around the family piano and at their Shiloh Baptist Church. Their uncle Bert taught them to sing harmony and soon the girls were performing at church and school concerts. At 15, Eleanor won first prize in an Edmonton amateur hour competition for her rendition of the jazz standard I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby.

Bitten by the performing bug, Eleanor was soon appearing on CFRN radio’s Good Morning, Neighbour and on stage with dance bands and orchestras at Edmonton’s Tivoli Ballroom. But she yearned for bigger opportunities and, in 1939, followed Ruby to Vancouver, where they were eventually joined by Pearl. The sisters formed a gospel group, the Swing Low Quartet, and began guesting on CBC Radio. Ruby became an accomplished classical pianist, while Pearl went on to sing as Black Cultured Pearl with Wynton Marsalis later in life. Pearl was also, notably, an aunt of Jimi Hendrix.

Eleanor put her career on hold in 1942 after meeting and marrying Richard Collins, a railway porter (he later managed a red cap service for air travellers). “Dick and I were lucky in love,” she later told the Vancouver Sun. “We wanted the same things, a home and a big family.” Four children – Rick, Judith, Barry and Tom – followed in quick succession. So, too, did the need for extra income to buy a house, and Eleanor’s return to work.

Eleanor put her career on hold in 1942 after meeting and marrying Richard Collins, a railway porter (he later managed a red cap service for air travellers). “Dick and I were lucky in love,” she later told the Vancouver Sun. “We wanted the same things, a home and a big family.” Four children – Rick, Judith, Barry and Tom – followed in quick succession. So, too, did the need for extra income to buy a house, and Eleanor’s return to work.

Adept at many vocal styles, from jazz and gospel to pop and show tunes, Ms. Collins joined the Ray Norris Quintet, whose CBC Radio program Serenade in Rhythm was broadcast overseas to Canadian troops during the Second World War. She also performed on the stage in Theatre Under the Stars productions of Kiss Me Kate and Finian’s Rainbow, the latter also featuring her children.

But with her radiant looks and engaging personality, Ms. Collins was destined for a career in television. In 1954, she appeared as a featured singer on the CBC variety show Bamboula: A Day in West Indies, the first Canadian television show with a mixed-race cast. She gained enough favourable notices that the following year she received an offer to star in her own CBC series, appearing with guitarist Chris Gage and reuniting with pianist Ray Norris and his band. Although The Eleanor Show only ran for the summer, it was a breakthrough at a time when few Black performers anywhere had been given such a showcase, and guaranteed Ms. Collins plenty of future work. The CBC show was reprised in 1964, as simply Eleanor, with the backing of the Chris Gage Trio.

Her TV appearances had a profound impact on viewers. “She was royalty to me, the queen of jazz vocals,” Don Thompson, then a budding musician in Powell River, B.C., and now an elder statesman of Canadian jazz, told The Globe and Mail. “She had a beautiful voice, warm and expressive, and you believed every word she sang.” Added Mr. Thompson: “I’d watch her perform with Chris Gage and his group and say to myself, ‘That’s what I want to do.’” Soon, Mr. Thompson was performing himself and appearing alongside her on TV shows, at Vancouver nightclubs and, in 1963, the city’s first summer jazz festival.

Red Robinson, the legendary Vancouver broadcaster who died last year, was another who fell under Ms. Collins’s spell. “As a young man in the 1950s, having just started my radio career, I was mesmerized by Eleanor Collins,” Mr. Robinson once wrote. “To me, she was Lena Horne and Sarah Vaughan all rolled into one. She had electric eyes and a voice to melt the hardest heart. I was in love with her.”

Red Robinson, the legendary Vancouver broadcaster who died last year, was another who fell under Ms. Collins’s spell. “As a young man in the 1950s, having just started my radio career, I was mesmerized by Eleanor Collins,” Mr. Robinson once wrote. “To me, she was Lena Horne and Sarah Vaughan all rolled into one. She had electric eyes and a voice to melt the hardest heart. I was in love with her.”

An international career beckoned, but Ms. Collins “never wanted a suitcase life,” as she put it. Committed to her husband and children, she preferred to stay in Canada. “Fame, you see, there’s a price to pay,” she told CBC’s Then and Now in 1988. “It’s lovely to be famous, but, what do you do when you take off the makeup, and you look at yourself in the mirror, and you remember you have youngsters at home, wonder what they are doing. You know, I could never do that.”

Her appearances became less frequent, although she continued performing for her church, on Remembrance Day events and at prestigious gatherings like the Canada Day celebration in Ottawa in 1975. She recalled looking out over 80,000 people on Parliament Hill, each one holding a candle, and getting emotional at the sight. “I was thinking of my parents who had decided Canada was going to be their country, because it was going to be better,” she told the Vancouver Courier. “And I suddenly realized how grateful I was to be Canadian.”

Mr. Pietropaolo recalls seeing Ms. Collins perform in 2014 at the age of 94, at a Black History Month musical celebration organized by gospel singer Marcus Mosely in Vancouver’s St. Andrews-Wesley United Church. “She carried herself with this immense presence, filling the entire room and commanding your attention with just her carriage,” Mr. Pietropaolo said. “But when she sang it gave me chills because she had the ability, even at that age, to transmit emotion with her voice and her whole physical performance. She was utterly captivating and I knew I was experiencing one of the great voices of the golden age of jazz.”

Mr. Pietropaolo recalls seeing Ms. Collins perform in 2014 at the age of 94, at a Black History Month musical celebration organized by gospel singer Marcus Mosely in Vancouver’s St. Andrews-Wesley United Church. “She carried herself with this immense presence, filling the entire room and commanding your attention with just her carriage,” Mr. Pietropaolo said. “But when she sang it gave me chills because she had the ability, even at that age, to transmit emotion with her voice and her whole physical performance. She was utterly captivating and I knew I was experiencing one of the great voices of the golden age of jazz.”

Aside from hard-to-find CBC transcription recordings with the Ray Norris and Dave Robbins quintets and with saxophonist Fraser MacPherson, Ms. Collins didn’t leave behind an extensive recording legacy. But she does appear on She Bop! A Century of Jazz Compositions by Canadian Women, a 2003 CD compilation, covering Ruth Lowe’s I’ll Never Smile Again. And there are numerous clips of her CBC performances on YouTube.

Crediting the love of her husband and family for her longevity and vitality, the always positive Ms. Collins continued living independently, with the help of her children, until a few days before her death when she entered Surrey Memorial Hospital and died of natural causes.

Ms. Collins was predeceased by Dick, her husband of 70 years, and leaves her four children, nine grandchildren and 15 great-grandchildren.

Originally published in The Globe and Mail on 9 March 2024