Music journalism, books and more

Toronto Songs: Neil Young's "Ambulance Blues"

Neil Young returned to the city of his birth in 1965, determined to break into Toronto’s flourishing music scene. He’d arrived with his Winnipeg group, the Squires, but their new folk-rock sound fell on deaf ears. Even changing their name to Four to Go failed to make a difference. So Young parted ways with his bandmates and launched himself as a solo folksinger.

Before leaving Winnipeg, Young had become enamored of Bob Dylan’s music and taught himself to play “Four Strong Winds,” Ian Tyson’s Canada-referencing response to “Blowin’ in the Wind.” He’d also encountered Joni Mitchell, who was performing at the Fourth Dimension coffeehouse with her husband. After the show, Young went up to Joni, told her he had a folk song of his own and played her “Sugar Mountain.” Mitchell was moved enough by Young’s lament for lost youth that she later wrote an answer song about the cycle of life: “The Circle Game.”

Breaking into the Yorkville scene wasn’t easy. Folk singers were competing with rock bands for stage time at the two dozen or more clubs and coffeehouses around the village. And a hierarchy existed, whereby coffeehouse owners relied on established U.S. stars or proven Canadian artists like Mitchell, Gordon Lightfoot and Buffy Sainte-Marie. Once you’d packed the house at the Riverboat, the Penny Farthing or the Purple Onion, you had officially made it. Cover stories in Hoot magazine and bookings at the annual Mariposa Folk Festival soon followed.

And a hierarchy existed, whereby coffeehouse owners relied on established U.S. stars or proven Canadian artists like Mitchell, Gordon Lightfoot and Buffy Sainte-Marie. Once you’d packed the house at the Riverboat, the Penny Farthing or the Purple Onion, you had officially made it. Cover stories in Hoot magazine and bookings at the annual Mariposa Folk Festival soon followed.

To keep body and soul together, Young took a low-paying job as a stock boy for Cole’s bookstore, at the corner of Yonge and Isabella. He also found an apartment at 88 Isabella Street, which made it handy for walking to work. Furnishings were sparse, but he did have a hot plate to cook on. Meals consisted mostly of baked beans on toast.

Holed up in his apartment, Young busied himself with writing songs. Among the compositions he penned at the time were “Runaround Babe” and “Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing” (later recorded with Buffalo Springfield). One of the more telling numbers, given his dire financial circumstances, was “The Rent is Always Due.”

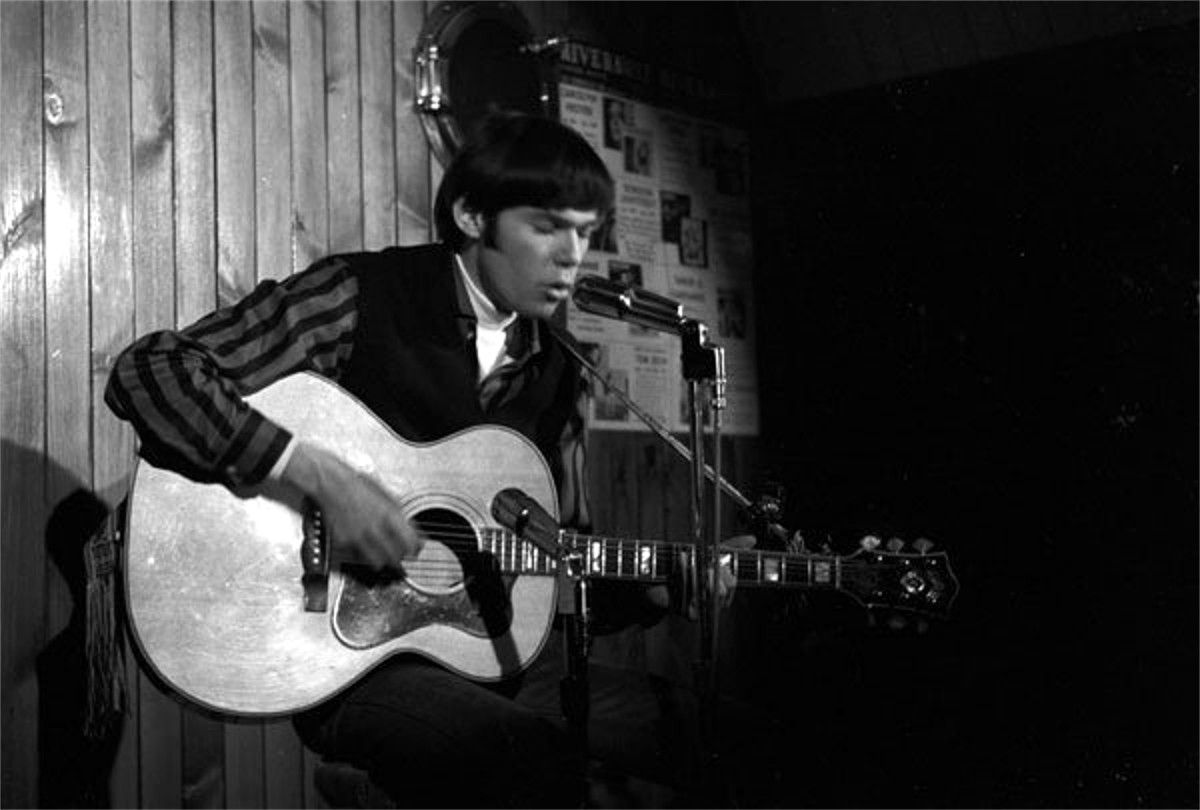

Most evenings, a tall, skinny figure carrying a 12-string guitar could be seen walking along Yorkville Avenue. It was Young, knocking on every coffeehouse door, trying to get himself a booking. He was denied at every turn. “They didn't take me seriously,” Young later complained. “They used to say, ‘Run along, kid.’” He had to settle for open mike nights at places like the Half Beat, the New Gate of Cleve and the Cellar. The closest he got to the Riverboat was playing at Monday’s “Hoot Night,” in a satirical group called the Public Futilities with folksinger Vicky Taylor and others.

Most evenings, a tall, skinny figure carrying a 12-string guitar could be seen walking along Yorkville Avenue. It was Young, knocking on every coffeehouse door, trying to get himself a booking. He was denied at every turn. “They didn't take me seriously,” Young later complained. “They used to say, ‘Run along, kid.’” He had to settle for open mike nights at places like the Half Beat, the New Gate of Cleve and the Cellar. The closest he got to the Riverboat was playing at Monday’s “Hoot Night,” in a satirical group called the Public Futilities with folksinger Vicky Taylor and others.

Taylor remembers that Riverboat owner Bernie Fielder was quite tolerant of the hoot-night silliness, but he had little time for Young as a singer. “One night they got into an argument and Bernie said that Neil howled like a dog and told him to take his horrible voice and never come in his club again,” Taylor recalls. “Neil said, ‘You know what, Bernie, some day you’re going to beg me to play here.’”

That day came a mere four years later. By then, Young was a major star. After bailing on Yorkville and a brief stint with Rick James in the Mynah Birds, he found fame in California—first with Buffalo Springfield and then as a solo artist. Young returned to play the Riverboat for an entire week in February 1969. “A Yorkville kid is coming home,” proclaimed a headline in the Toronto Star. A review in The Globe & Mail praised his performance and described him as “a singer of conviction with a rare sense of purpose.” For Young, it was sweet justice (40 years later, underscoring the importance of that dramatic homecoming, he released Live at the Riverboat 1969).

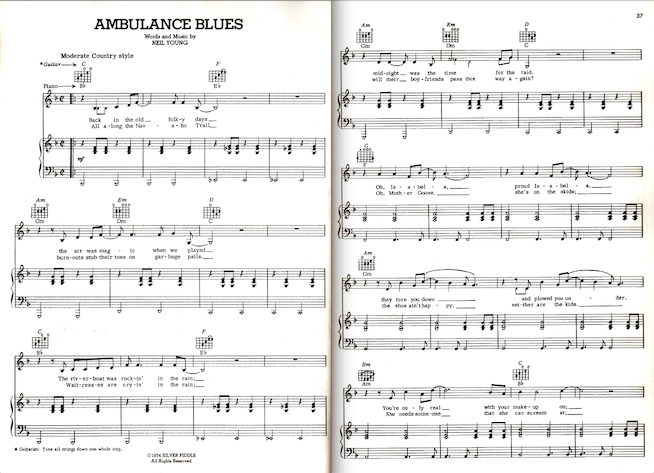

In the summer of ’74, Young released his fifth solo recording, On the Beach. The last song on the album was “Ambulance Blues,” a nine-minute opus that fondly references his time in Yorkville (by this point, his memories had clearly mellowed). “Back in the old folky days,” he sings, “the air was magic when we played. The Riverboat was rocking in the rain; midnight was the time for the rain.” Later in the song, Young laments the changes to his old neighborhood. “Old Isabella, proud Isabella,” he opines, “they tore you down and plowed you under.”

One of Young’s richest and most metaphorical works, the backward-glancing “Ambulance Blues” not only memorializes Yorkville’s fabled club, its closing lines also mention Toronto directly: “Well, I’m up in T.O., keepin’ jive alive,” Young sings, “And out on the corner it’s half past five.” It’s unapologetically nostalgic and yet deals thoughtfully with the inevitable process of aging, the end of the hippie era, the passing of a generation and disillusionment with the establishment. Ultimately, it’s another song of lost innocence—a grown-up look at the same topic covered in “Sugar Mountain.” And it has been rightly hailed as a masterpiece.

One of Young’s richest and most metaphorical works, the backward-glancing “Ambulance Blues” not only memorializes Yorkville’s fabled club, its closing lines also mention Toronto directly: “Well, I’m up in T.O., keepin’ jive alive,” Young sings, “And out on the corner it’s half past five.” It’s unapologetically nostalgic and yet deals thoughtfully with the inevitable process of aging, the end of the hippie era, the passing of a generation and disillusionment with the establishment. Ultimately, it’s another song of lost innocence—a grown-up look at the same topic covered in “Sugar Mountain.” And it has been rightly hailed as a masterpiece.