Music journalism, books and more

Feature Article: The Fight Over Golden Oldies

Even from an artist renowned for outrageous behavior, the action was a shocking sight. In August, 1984, Richard Penniman—better known as Little Richard, the flamboyant 1950s rocker—began picketing an office building in downtown Los Angeles. The rock star was not on strike; he was on a crusade. The offices belonged to ATV Music Corp., one of the world’s largest song publishers. Little Richard’s claim: that ATV, along with Specialty Records and Venice Music, owed him millions of dollars in royalties for “Tutti-Frutti,” “Good Golly Miss Molly” and other classic Little Richard hits. Four months later his $115-million lawsuit against those companies was thrown out of U.S. Federal Court.

Now, Little Richard, 54, is pondering his next move. But in a recent Maclean’s interview he said bitterly, “I was taken for everything except my toenails—and they would’ve got them as well, but they were too short to cut.” Little Richard has a new recording contract with Warner Bros, and says that Lifetime Friend, his new album on that label, will be the first to earn him money in 30 years of recording.Nor is Little Richard’s case unique. The history of rock ’n’ roll is littered with artists who, through naïveté, deception or just plain bad deals, signed contracts they now regret. As a result, they lost either lucrative copyrights on their songs or royalty payments on their recordings. Without the advice of lawyers or managers, some performers sold the copyrights or recording royalties for a lump-sum cash advance. Those who lost their rights to future payments were sometimes told it was impossible to win them back. And their efforts to do so were complicated if the company with which they had signed went bankrupt or became absorbed by a larger conglomerate.

But now, as nostalgia for rock’s early sounds turns songs of that period into hot properties, the question of who owns what is hotter than ever. When featured in film sound tracks and television commercials, some of rock’s golden oldies fetch as much as $200,000 in licensing fees—for whoever owns the rights. Contemporary artists have learned to be cautious about signing contracts. “Many young artists are worried about signing something that kisses a Q lot of potential income good| bye,” said Clark Miller, one of Canada’s top entertainment lawyers. Miller, who conducts workshops with Canadian musicians to advise them about contractual matters, says songwriting is still the biggest money-earner for a successful artist. The reason: writers make money as soon as the song is performed or receives airplay.

Industry observers estimate that Canadian rock star Bryan Adams earned $150,000 in publishing royalties alone from “Heaven,” one of four hits he wrote for his 1985 album, Reckless. On the other hand, an artist who records other people’s music does not begin to earn royalties from his discs until he first repays the production costs of an album to the record company. Said Miller: “A copyright of a song is something that you own, that you can actually take to the bank.”

Even the biggest and presumably best-advised artists have made deals they now regret. Since 1969 Paul McCartney has tried unsuccessfully to recover ownership rights to the highly prized Beatles’ songs he wrote with John Lennon, currently owned by ATV. The Beatles’ songs are part of the corporation’s catalogue, now valued at more than $65 million.

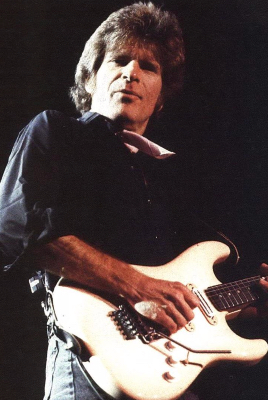

Meanwhile, country rocker John Fogerty refuses to perform “Proud Mary” and other hits of his 1960s band Creedence Clearwater Revival because it would benefit Fantasy Records, for whom he had agreed in 1968 to record several albums. Fogerty’s Creedence songs earned more than $200 million worldwide, but according to Fogerty the contract only gave the group a low royalty rate. As well, on the advice of an Oakland, Calif., accountancy firm, the band’s savings were invested in a Bahamian bank tax shelter that subsequently lost its charter—and the Creedence funds.

By 1980, still owing Fantasy three more albums, Fogerty was so anxious to break his contract that he gave Fantasy his share of Creedence royalties in exchange for freedom. Meanwhile, he sued his accountants and in 1983 won a settlement of $5.5 million; the case is under appeal. Yet Fantasy still earns money on Creedence recordings. As a result, Fogerty told Maclean's, “playing those songs today is too painful for me because it only lines someone else’s pockets.”

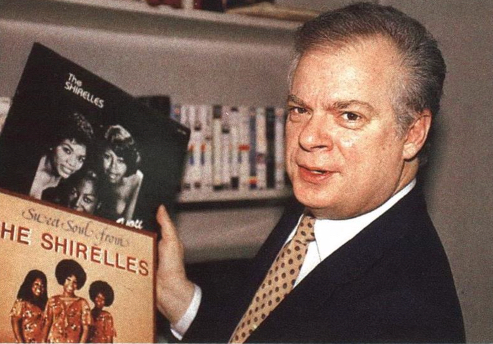

At last, however, artists have someone to champion their cause. He is Chuck Rubin, described by The New York Times as the "white knight of rock.” Rubin, 48, runs the Artists Rights Enforcement Corp., a New York firm that seeks to regain royalties for performers. His list of about 200 clients reads like a Who's Who of early rock ’n’ roll, with enough vintage pop songs to their credit to fill a rec room full of jukeboxes. Among them: The Shirelles (“I Met Him on a Sunday”); Huey (Piano) Smith (“Sea Cruise”); The Marvelettes (“Please Mr. Postman”); and the estate of Clyde McPhatter (“Money Honey”).

At last, however, artists have someone to champion their cause. He is Chuck Rubin, described by The New York Times as the "white knight of rock.” Rubin, 48, runs the Artists Rights Enforcement Corp., a New York firm that seeks to regain royalties for performers. His list of about 200 clients reads like a Who's Who of early rock ’n’ roll, with enough vintage pop songs to their credit to fill a rec room full of jukeboxes. Among them: The Shirelles (“I Met Him on a Sunday”); Huey (Piano) Smith (“Sea Cruise”); The Marvelettes (“Please Mr. Postman”); and the estate of Clyde McPhatter (“Money Honey”).

A former booking agent, Rubin learned that a longtime musician client, Wilbert Harrison, had never received royalties from his 1959 No. 1 hit recording of “Kansas City.” Harrison’s problem: two different record companies were squabbling over who had rights to his version of the song, written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. After a four-year court case that began in 1978, Rubin helped Harrison acquire ownership of the master recording. Harrison, now 58, earns between $6,500 and $10,000 a year from the song—a much-needed supplement to his journeyman musician’s income. Said Rubin: “I thought Wilbert’s case was unique, but I soon learned that it’s unique if an artist from that period was paid at all.” Rubin also recalls the day New Orleans rhythm-and-blues artist Huey (Piano) Smith told him how he had lost the rights to his songs “Sea Cruise” and “Don’t You Just Know It.” According to Smith, his lawyer-manager told him that the songs were almost worthless and persuaded him to sell them to a willing buyer. Rubin’s detective work revealed that the customer was the lawyer’s wife, using her maiden name. Smith now earns royalties on his songs for the first time.

An even more bizarre case involves the estate of Frankie Lymon, the teenage singing sensation who died in 1968. Lymon and his group, the Teenagers, enjoyed a Top 10 hit in 1956 with “Why Do Fools Fall in Love,” which later was used on several TV shows. Rubin successfully won performance royalties for the artists, including Lymon’s estate, in 1982. But it was not until a year later, while pursuing further royalties, that Rubin located Lymon’s widow, Emira Lymon, a schoolteacher in Augusta, Ga. She was naturally delighted, but surprised that she was entitled to any royalties; she had been told by Lymon’s attorney that she had no legal claim. When Rubin tried to help her renew the claim on her husband’s composition, he discovered that Lymon’s record company owner had come to court with two other women, each claiming to be the singer’s widow and heir. The case is now pending in the New York courts. Rubin estimates that the royalties in question could be worth more than $1.4 million.

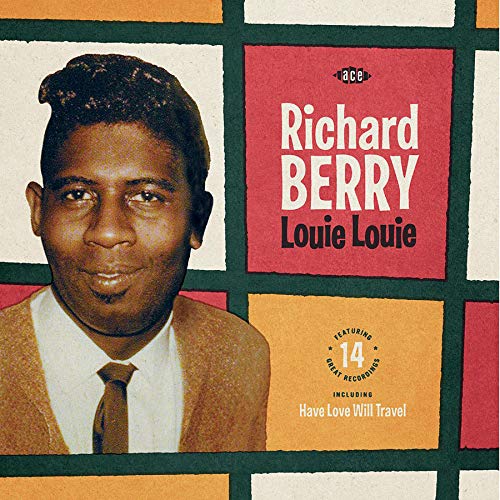

In some cases the loss of rights was clearly the artist’s own fault. In 1957 Richard Berry sold copyrights to seven of his songs to his publisher for $750 because, he said later, he needed money to get married. One of those songs, a three-chord tune called “Louie Louie,” later became a rock classic, with more than 400 recorded versions. Had Berry retained ownership, industry experts say that he would have earned about $5 million from the song. But his story has a happy ending. Last year, after seven years of perseverance, Berry, 51, won his share of the copyright back and is now entitled to future payments.

In some cases the loss of rights was clearly the artist’s own fault. In 1957 Richard Berry sold copyrights to seven of his songs to his publisher for $750 because, he said later, he needed money to get married. One of those songs, a three-chord tune called “Louie Louie,” later became a rock classic, with more than 400 recorded versions. Had Berry retained ownership, industry experts say that he would have earned about $5 million from the song. But his story has a happy ending. Last year, after seven years of perseverance, Berry, 51, won his share of the copyright back and is now entitled to future payments.

Other performers, including Paul McCartney, have had less luck. Although McCartney, a multimillionaire, has been able to buy song catalogues of Broadway show tunes and those of his idol, 1950s rocker Buddy Holly, he has always been outbid by publishing conglomerates for his own material. And he lost the rights to such Beatles’ hits as “Yesterday” to his friend Michael Jackson—two years after McCartney convinced Jackson over a private dinner of the investment value of copyright ownership. “More and more,” says lawyer Miller, “songwriters are realizing that if they’re not careful, they can fall into all those famous pitfalls.”

Originally published in Maclean’s magazine March 2, 1987