Music journalism, books and more

Liner Notes: True North at 50

Everything has to start somewhere. For True North Records and Bruce Cockburn, the beginning can be traced to April 7, 1970. On that spring day in Toronto, a remarkably mild and sunny one, by all accounts, True North was auspiciously born with the release of Cockburn’s first solo album. The reviews for the record were universally ecstatic. One newspaper said it deserved “nothing but praise,” while another called the album “quite simply the best thing to happen in Canadian music since Joni Mitchell.” It was the start of a long and fruitful partnership between label and artist. Over the next 50 years, True North would issue another 33 albums by the acclaimed singer-songwriter (along with hundreds by other artists) and there’s no sign that either is stopping.

A 50th anniversary is a significant milestone. Not many record companies achieve a half-century of history these days and few musicians remain vitally productive over a 50-year period. To celebrate, True North offers this lavish box set with three of Cockburn’s most important recordings: Bruce Cockburn (catalogue # TN1), The Charity of the Night (TN150) and Breakfast in New Orleans, Dinner in Timbuktu (TN183)—all released in special coloured pressings and, in the case of Charity and Breakfast, available on vinyl for the first time.

Now, for a little more history. True North’s origins can be traced to Toronto’s hippie enclave of Yorkville, where Bernie Finkelstein made a name for himself as the manager of two highly successful Canadian rock bands: the Paupers and Kensington Market. When the latter broke up in 1969, Finkelstein and the Market’s Luke Gibson decamped to a rural commune in Killaloe, Ont., 350 km northeast of Toronto. While escaping the psychedelic haze that hung over Yorkville, Finkelstein had a vision: create a home for Canadian singer-songwriters. He returned to Toronto with a plan to start a record company. He even knew what he’d call it.

“I took the name right out of Canada’s national anthem,” Finkelstein admits today. “It just popped into my head and I thought it would make a great name for what I wanted to do. I liked the double meaning of the two words, that they stood for Canada but also something unerring. That was my interest—releasing quality records that would stand the test of time.”

It wasn’t long before Finkelstein knew which artist was going to be the first on his fledgling label. He’d been introduced to Bruce Cockburn by the Market’s Gene Martynec and caught a performance by him at the Pornographic Onion, a coffeehouse on the campus of Ryerson University. Finkelstein recalls being impressed with Cockburn’s guitar playing and two songs in particular, “Musical Friends” and “Going to the Country,” which to him sounded like they could be hits, given the proper treatment. When Cockburn agreed to Finkelstein’s record deal offer, his condition was that he record his songs solo, with minimal accompaniment. Finkelstein reluctantly agreed.

Recorded at Toronto’s Eastern Sound studio over three days in late 1969, with production by Martynec, Bruce Cockburn’s warm acoustic songs of an inquisitive, pastoral and spiritual nature offered a welcome antidote to the anxious cacophony of the times. Years later, looking back on the period the album was made, Cockburn called it “a time of reaction, trying to leave behind the years of questionable rock bands, trying to clear out psychedelic decadence. Looking for purity in nature. Looking for connections behind things.”

The album included Finkelstein’s favourite tracks, although they wound up much simpler than he’d envisioned. “Musical Friends” and “Going to the Country” both became hits, reaching the Top 40 on RPM’s adult contemporary chart. “Going to the Country” captured the zeitgeist of the era’s back-to-the-land movement. So, too, did the cover’s artwork, by Toronto illustrator Bruce Meek, now a renowned Venice-based artist. People were starting to leave the cities, Cockburn told the CBC in 1970, in search of solitude. He added: “In the city I tend to shut myself off from detail a lot because there’s so much of it and a lot of is distracting. In the country I become aware of detail and sounds. There’s a continuous roar in the city, but there’s a continuous song in the country and you become aware of all the different melodies and components of that music.”

The album included Finkelstein’s favourite tracks, although they wound up much simpler than he’d envisioned. “Musical Friends” and “Going to the Country” both became hits, reaching the Top 40 on RPM’s adult contemporary chart. “Going to the Country” captured the zeitgeist of the era’s back-to-the-land movement. So, too, did the cover’s artwork, by Toronto illustrator Bruce Meek, now a renowned Venice-based artist. People were starting to leave the cities, Cockburn told the CBC in 1970, in search of solitude. He added: “In the city I tend to shut myself off from detail a lot because there’s so much of it and a lot of is distracting. In the country I become aware of detail and sounds. There’s a continuous roar in the city, but there’s a continuous song in the country and you become aware of all the different melodies and components of that music.”

Other tracks like the questing “Spring Song,” with its droning guitar, and the haunting “Thoughts on a Rainy Afternoon,” built on a descending melody, reflect the beginnings of a spiritual direction that figured on Cockburn’s next two albums and became more prominent on his later recordings. “Eastern philosophies were there,” Cockburn admits. “I wasn’t a Christian yet although I was heading that way. And I [had] been exposed to aspects of Buddhist teachings, first through the Beat writers [and then] the Sutras.”

Fast forward over two decades to the release of The Charity of the Night and Breakfast in New Orleans, Dinner in Timbuktu, his 19th and 20th albums respectively, and Cockburn’s wanderings—literally and spiritually—are more pronounced. The folky flavor of his first recording is mostly gone, replaced by jazzy, bluesy and African influences. The two albums are included here for reasons other than just the fact they haven’t been released on vinyl before. Taken together, Charity and Breakfast are companion recordings, co-produced for the first time by Cockburn and Colin Linden. The link between the two, Cockburn explained, was that Charity was about “the search for light in the dark,” while Breakfast was about “healing.” And the two albums are related geographically as well as stylistically. The former was mixed in New Orleans, while the latter features a slow, shimmering version of “Blueberry Hill,” the classic by New Orleans legend Fats Domino, and another song set in the Big Easy. Charity includes two songs written in Mozambique in southeast Africa and the music on Breakfast was partly inspired by a trip Cockburn had taken to Mali in west Africa.

Fast forward over two decades to the release of The Charity of the Night and Breakfast in New Orleans, Dinner in Timbuktu, his 19th and 20th albums respectively, and Cockburn’s wanderings—literally and spiritually—are more pronounced. The folky flavor of his first recording is mostly gone, replaced by jazzy, bluesy and African influences. The two albums are included here for reasons other than just the fact they haven’t been released on vinyl before. Taken together, Charity and Breakfast are companion recordings, co-produced for the first time by Cockburn and Colin Linden. The link between the two, Cockburn explained, was that Charity was about “the search for light in the dark,” while Breakfast was about “healing.” And the two albums are related geographically as well as stylistically. The former was mixed in New Orleans, while the latter features a slow, shimmering version of “Blueberry Hill,” the classic by New Orleans legend Fats Domino, and another song set in the Big Easy. Charity includes two songs written in Mozambique in southeast Africa and the music on Breakfast was partly inspired by a trip Cockburn had taken to Mali in west Africa.

Charity features some of the best songs in Cockburn’s massive catalogue. It also benefits from the exceptional musicianship of Gary Burton on vibraphone, Rob Wasserman on bass and Gary Craig on drums. The urgent, driving opener “Night Train” sets the tone for the album. Like all of the songs on the album, it was written in the evening, following the chaos of the day, and is also set at night. When asked what the song was about, Cockburn replied: “A large quantity of absinthe!” The track became a radio hit in Canada. “The Whole Night Sky,” an achingly beautiful affirmation of faith that can leave one looking heavenward and features the soulful slide guitar of Bonnie Raitt. “Pacing the Cage,” Charity’s folkiest song, in the style of “All the Diamonds,” has become a favourite of fans of both Cockburn and Jimmy Buffett, who covered it on his Beach House on the Moon album.

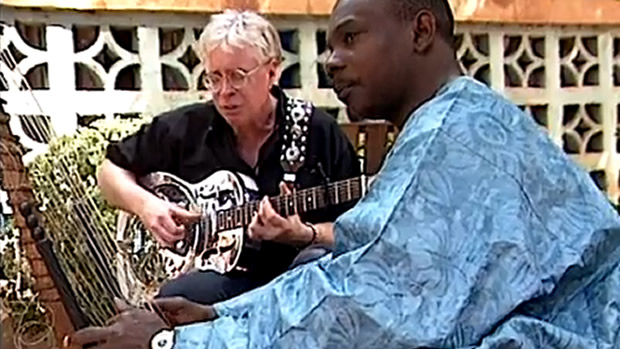

Breakfast opens in New Orleans with the funky “When You Give It All Away,” and closes in Timbuktu with the cascading “Use Me While You Can,” whose lyrics give the album its title. Both songs are manifestations of Cockburn’s reportage approach to lyric writing and both feature the sultry harmonies of Lucinda Williams. The album is a transcontinental journey that traces the roots of the blues back to Africa. Cockburn had traveled to Mali in February 1998 for River of Sand, a documentary about the country’s culture and people as they fight the encroaching desert. During the making of the film, he met and performed with legendary musicians Toumani Diabate and Ali Farka Touré. And sounds of the kora, a 21-string African harp, and African-style percussion are prominently threaded throughout the album.

Breakfast opens in New Orleans with the funky “When You Give It All Away,” and closes in Timbuktu with the cascading “Use Me While You Can,” whose lyrics give the album its title. Both songs are manifestations of Cockburn’s reportage approach to lyric writing and both feature the sultry harmonies of Lucinda Williams. The album is a transcontinental journey that traces the roots of the blues back to Africa. Cockburn had traveled to Mali in February 1998 for River of Sand, a documentary about the country’s culture and people as they fight the encroaching desert. During the making of the film, he met and performed with legendary musicians Toumani Diabate and Ali Farka Touré. And sounds of the kora, a 21-string African harp, and African-style percussion are prominently threaded throughout the album.

Cockburn described Breakfast as cheerful, not focused so much on darkness. “[It] has a lot more light in it,” he acknowledged, “or at least sunlight, even if it’s coming through a sandstorm.” The album features “Last Night of the World,” a wistful apocalyptic musing about sharing champagne with a friend. It became one of Cockburn’s biggest hits, topping the U.S. Triple A radio charts. There’s a joyousness to songs like the erotic “Mango,” featuring the sensuous vocal harmonies of Cowboy Junkies’ Margo Timmins, who duets with Cockburn on “Blueberry Hill.” The latter song also features the shimmering playing of stellar organist Richard Bell (Full Tilt Boogie, The Band, Blackie & the Rodeo Kings) who passed away in 2007.

Although it doesn’t delve into political issues like certain other Cockburn albums, Breakfast does include “Let the Bad Air Out,” a biting critique of “traitors in high places” and a Parliament that “smells like something died.” Over a percussive backdrop, Cockburn quotes Chuck Berry while expressing his disgust with deception and duplicity. “Open up the window,” he sings, “let the bad air out.” Meanwhile, “The Embers of Eden” references the earth’s burning rainforests as seen from space. But it’s not a Cockburn song about ecological destruction like “If a Tree Falls.” Instead, the striking image serves as a potent metaphor for a dying personal relationship.

As a trio of memorable albums, Bruce Cockburn, The Charity of the Night and Breakfast in New Orleans, Dinner in Timbuktu represent a highwater mark in Cockburn’s exceptional career. Packaged here, they serve as a fitting celebration of the 50th anniversary of True North Records, a label founded with the mission of delivering quality records that stand the test of time.